|

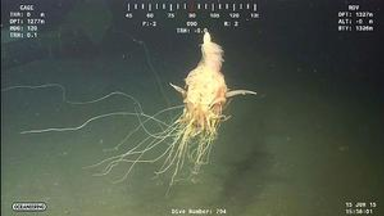

With an estimated one million species of animal living in the ocean, the diversity of ocean life is truly amazing! While most of us might think about sea turtles, dolphins or the biggest sea creature of all, the blue whale, as our favourite underwater wonder, not every species in the ocean is quite so… photogenic. Most of the spookiest sea creatures live deep beneath the ocean surface, where the sunlight barely reaches. This environment houses some of the most interesting and ugliest(!) animals that have only recently been discovered by scientists due to the remarkable conditions where they exist and thrive. This spooky season, we want to share with you some of the spookiest sea creatures! Be brave and dive into our top ten list! 10. CoffinfishCoffinfish, colloquially known around Australia (where they are most commonly found) as Sea Toads, are benthic (bottom-dwelling) fish with the ability to use their fins to walk along the seafloor! They are ambush predators, whose facial expressions typically look really sad, because of the shape of their mouths. However, they are able to inflate their body with water which allows them to hold their breath for up to four minutes!! This is supposedly so that they can conserve energy when food on the ocean floor is scarce. And when they do… they look kind of like a cute balloon?! (Photo credit: National Geographic) 9. Sarcastic Fringehead Although completely harmless to humans unless provoked (they have been known to threaten scuba divers who get too close…), the Sarcastic Fringehead is well known for opening its huge mouth to fend off other ocean-dwelling critters when provoked or agitated. They live in burrows or tube-like structures created by other animals, such as burrowing clams or snail shells. Their specifically-designed jaws fan out to the side when they open their mouths, which makes them appear much larger and more intimidating. If one Sarcastic Fringehead challenges another, the two will “kiss” by aggressively pressing their open mouths against each other until one finally gives up and swims away! (Photo: WikiMedia) 8. Barreleye This deep sea fish is transparent and has the ability to move its eyes 360 degrees so they can see what’s going on (and what’s for dinner) even when it’s behind them! Scientists only fully discovered this species in 2009, when they identified that their eyes can fully rotate inside of their head. Another quirky trait of the Barreleye is that it engulfs its prey fully! The Barreleye, like many species on this spooky list, lives deep in the ocean where there is hardly any light, so their specially designed eyes allow them to see even in almost complete darkness. (Photo: MBARI) 7. Vampire Squid Unlike other squid (which can be surprisingly aggressive as tiny sea critters go!), Vampire Squid are surprisingly docile (no, they don’t suck the blood of their prey!). Vampire Squid actually feast mainly on “marine snow”, decaying organic material that falls down to the ocean floor. The spookiest feature of the Vampire Squid is its strange appearance, notably it’s umbrella-like tentacles! (Photo: ThoughtCo) 6. Goblin Shark You guessed it, these guys are ugly. Nonetheless, they use their impressive ugliness to their advantage; they use their elongated, flattened snout to seek out their prey with specialized sensing organs to sense electric fields in the darkness of the deep ocean, and they can extend their jaw the entire length of their snout to catch their prey (mainly squid, fish and crustaceans) with their 50 thin, sharp teeth! Thankfully they only grow to be 8-11 inches long! (Photo credit: Diane Bray, Museum Victoria) 5. Northern Stargazer Only found in the eastern United States, this frightening fish burrows itself in the sand to camouflage and can use its side fins as shovels to quickly burrow and hide beneath the sand. When unsuspecting prey comes near, the stargazer has a special organ on its head that can deliver an electric shock that stuns and confuses the prey and electrically shocks it into submission. Seems like not only is this guy pretty painful to look at, but might be pretty painful to encounter on the bottom of the ocean... (Photo: Huffington Post) 4. Deep Sea Anglerfish Yet another deep-sea carnivore, this anglerfish, also known as the humpback anglerfish, has to be one of the ugliest and spookiest creatures on the planet! Most famous for the bioluminescent growth on their heads, which lures their prey towards them, and to their death, deep in the darkness of the ocean. This lure is filled with bacteria, which the fish use to make their own light. They use a muscular flap of skin to either expose or hide the glowing lure. Pulsing the light and slowly moving it back and forth attracts all kinds of prey. Creepy, right? Not to mention their razor sharp, translucent teeth and their dead-looking eyes... (Photo: Oceana) 3. “Flying Spaghetti Monster” Bathyphysa conifer Belonging to the Siphonophores, a group of animals including corals and jellyfish, is probably one of the weirdest creatures floating around in the ocean; first captured on video by oil and gas workers in 2015, at around 1220m depth. It has been nicknamed the “flying spaghetti monster” for its white, noodle-like appearance. Perhaps the quirkiest fact about these guys is that Siphonophores actually clone themselves in order to grow! Instead of a single body, one siphonophore is a whole tightly knit colony of many organisms, sometimes several thousands! (Photo: National Oceanography Centre) 2. Skeletal Jellyfish Also known as the crystal jellyfish, this ghostly, translucent critter can give off a green-blue glow when provoked or disturbed, due to the 100 or more tiny, light-producing organs that surround its outer bell. Glow in the dark and a skeleton costume? This guy is permanently embracing spooky season down there on the ocean floor! (Photo: Hiroya Minakuchi) 1. Ghost Fish Perhaps not as terrifying as some of the others, but by far my favourite spooky sea creature is this little guy; the ghost fish! Spotted alive and swimming for the very first time by a team of NOAA research scientists in 2016, we are still learning all about the ghost fish, which was seen swimming in the Mariana Trench at around 2500 m depth!! With translucent, scale-less skin and small colourless eyes, the ghost fish is undeniably bizarre and gives me perfect spooky season vibes! (Photo: Weather Channel)

0 Comments

June 16th is World Sea Turtle Day! To celebrate, let's talk about a sea turtle that’s a bit closer to home than you may have realized. Canadian Sea Turtles When you picture a sea turtle habitat, I bet you’re picturing a lush tropical beach with crystal clear turquoise water. That’s not incorrect! We can find many different sea turtle species in the tropics. However, there is one special species that likes to visit Nova Scotia’s waters on an annual basis. Welcome to the wonderful world of the leatherback sea turtle! The presence of leatherback sea turtles in Nova Scotia is a relatively new finding in the scientific world, although fishermen all across Atlantic Canada reported sightings of these turtles long before the first scientific article was published. Named after the thick skin that covers their shells, leatherback sea turtles visit Atlantic Canada and the North Atlantic ocean as part of their migration route. They can be spotted in Atlantic Canadian waters during the summer months, and then during the fall they begin their journey back down to the tropics to mate and nest. Leatherbacks are Super Cool Not only is it awesome that Canada has its own sea turtle species, but we actually have (in my opinion) the most fin-tastic sea turtle! Although there are many reasons as to why the leatherback is so incredible, I’m going to highlight three of my favourite reasons below. Their Size Size comparison of all seven currently living species of sea turtle, and one extinct species. Photo credit: Smithsonian Not many people realize just how big sea turtles are. Green sea turtles, which are a popular tropical sea turtle species and sometimes found in Atlantic Canada, are typically 3 to 4 feet long and weigh over 300 pounds. This is similar to the size of a baby elephant! However, Green sea turtles have nothing on leatherback turtles. Leatherback sea turtles are actually one of the largest reptiles on earth! They can reach over 2 meters (6 feet) in length and weigh over 2000 pounds. The only reptile to come close to the size of a leatherback sea turtles is the salt water crocodile! What They Eat Leatherback eating jellyfish in Atlantic Canada Photo credit: Lorne Bonnell from CBC news Leatherback turtles do not have a very diverse diet. In fact, they mainly only eat one thing. Based on how big they are, be you may think they eat huge fish or full lobsters – but the reality is a bit more strange! Leatherback sea turtles follow currents from the tropics all the way to Nova Scotia to find one thing: Jellyfish! You read that right, these massive turtles only eat jellyfish and other jellyfish-like animals like tunicates and ctenophores. A single jellyfish doesn’t provide very much nutritional value, so leatherback sea turtles will eat up to their body weight in jellyfish every day! Think about how many more jellyfish would fill our ocean if we didn’t have turtles eating 2000 pounds of jellyfish daily. Thank you leatherbacks! The Pink Spot Leatherback sea turtle with visible pink spot on the top of its head! Photo credit: S. Bonizzoni The last cool leatherback fact I’m going to highlight is their pink spots. Leatherbacks have a very special characteristic that helps us identify them from afar (it comes in handy when trying to spot a leatherback from a boat to tag!). On the back of every leatherbacks head is a pink dot. This is actually an exposed part of their brain! Although science is still debating what the actual function of this pink spot is it is theorized it helps identify light and may play a role in leatherback migration! Perhaps a built in GPS? Turtles in Danger Unfortunately, similar to other sea turtles species, leatherback sea turtles population numbers have declined, and the species is currently listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. These turtles face many threats including fisheries bycatch, habitat loss, and plastic pollution. On the plus side, if you’re looking to help leatherbacks you have already have helped just by reading this far into my blog post! Not many people realize how cool leatherback sea turtles are and that they are part of our maritime family. The more people that realize these turtles share our waters and how amazing they are, the better chance the turtles will have for future protection measures. If you are interested in doing more for leatherback sea turtles check out the Canadian Sea Turtle Network who are doing great work for sea turtles in Canada. If you’re looking for even more leatherback content checkout this fact page by NOAA Fisheries. Feel free to ask questions about leatherbacks in the comments!  Lauren is a part of the Communications Committee for Back to the Sea and just recently finished her undergraduate degree in marine biology and sustainability at Dalhousie. Lauren is extremely passionate about ocean conservation and loves to share this passion by educating everyone around her on the wacky and amazing species that call the ocean home! by Leah Robertson “What are those jellyfish in the water?!” Every spring and early summer, Nova Scotia gets a group of fabulous visitors in our waters. I have seen so many people hanging their head over the side of the Halifax boardwalk trying to get a better look at these tiny mysteries. But today we are breaking the mystery for you. So what are they? They go by many names including ‘disco jellies’, ‘ctenes’, or ‘comb jellies’, but their mouthful of a scientific name is Ctenophora. [Pronounced “teen-OH-four-ah”]. Now these extravagant little jellies are many things but the one thing they are not is jellyfish! Sea Gooseberry Ctenophora (we have these in Nova Scotia too!) (photo: copyright Kare Telnes from seawater.no) While Ctenophora may have the gelatinous form we are used to seeing in ‘jellyfish’ (which is classified scientifically at Cnidiarians), there are a few hallmark reasons that make them their own phylum and a very fun animal to observe: Don’t fear! Ctenophora can’t sting you. This is one of the most noteworthy differences between Ctenophora and Cnidarians (aka jellfyfish!). They do not have what are called cnidocytes which deliver the stringing feeling we get when we touch the tentacles of a jellyfish. However, even though they can’t sting you we still recommend observing them at a safe distance. Since ctenophora have a soft jelly-like body it is very easy to injure these little wonders. How do they get around? I am so glad that you asked! Ctenphora are the largest organisms that move by ‘cilia’. Cilia are very tiny hairs that typically bacteria use to move around. Ctenophora have eight rows of the cilia attached to their body which move in tandem to help them get around. Slow and steady wins the race with ctenes! See how they move here. Lobed Comb Jelly (Photo: Monterey Bay Aquarium) Hey! Why do they look different? Both of these pictures are ctenophora, but are different species. Ctenophora really do come in all shapes and sizes. Ctenophora have lots of different species and some have beautiful long tentacles and some are nice and oval shaped without any additional appendages. Often in Nova Scotia, we have multiple different species of ctenohpora in our waters at the same time. What is the RAINBOW? Ctenophora are often mistaken are being “bioluminescent” which is the process where organisms give off their own light. Now some species of Ctenophora are biolumensect, but most often if you are seeing beautiful rainbow colours it is from the light refracting off the tiny beating cilia! We love to call them disco jellies for this reason! What do you think their favourite disco song is to synchronously move their rows of cilia to? (My bet is on Stayin’ Alive!). Ctenophore inside another ctenophore, ctenophore are sometimes eaten by larger fish, or larger ctenophores (photo: Magali Grégoire) They are CARNIVORES? Yes! While tiny and innocent looking, ctenophora do eat other animals (albeit animals tinier than them). They generally eat small zooplankton. But comb jellies themselves are often eaten by larger fish! You can watch this video to see them engulf food. So next time you see a comb jelly in the water, make sure you tell a friend all about these often-mistaken but amazing animals!

by Kayla Hamelin When you live in Nova Scotia, it is obvious that fishing is an important part of the culture and economy of Atlantic Canada. Fishing vessels fill our harbours. Folks head down to their local pier – rod in hand - to cast a line and see what bites. Seafood restaurants and markets abound. People fish for fun, for food, and for work. As I begin my PhD research in fisheries science, I am gaining a greater appreciation for the wide range of species harvested off our shores. Out there under the “big blue blanket” are incredible invertebrates like the gangling snow crab, and formidable flatfish like the massive Atlantic halibut. However, there is one species that has really charmed me – the Atlantic mackerel, also known as Scomber scombrus. The more I learn about these fin-tastic friends, the more I am hooked! Mackerel are a marine, pelagic fish, which means that they live in the open water column of the ocean, rather than on the bottom or at the shore. They have beautiful bodies well-adapted for camouflage in the ocean, with shimmery blue on their backs, silvery undersides, and squiggly stripes down their backs and flanks. You may notice the tiny finlets (mini, nonretractable fins) on their caudal peduncle (a funky name for the area where the body meets the tail fin). These finlets help with their high-performance swimming and are a feature shared with some of the larger members of their Scombridae family, including the mighty tunas and bonitos. Mackerel are relatively small, measuring up to about 40 cm (a bit more than a foot) in length and about 1 kg in mass. However, there is strength in numbers, and these schooling fish like to swim together in large groups to stay safe from predators. Fun fact: unlike many of their relatives, mackerel do not have a swim bladder, the gas-filled organ that helps many fish to control their buoyancy. Without a swim bladder, mackerel must follow Dory’s advice and just keep swimming! Atlantic mackerel can be found on both sides of the Atlantic, so we share this special species with our friends in Europe. Here in North America, they range from the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador in the north all the way down to North Carolina in the south. Mackerel always play an important role in the marine ecosystem. They are known as “forage fish” because they act as an important food source for larger animals such as marine mammals, sharks, and other larger fish. Mackerel themselves prefer to eat small invertebrates such as zooplankton. As a result, they act as an important link in the ecosystem, passing food energy up through the food web to the top marine predators. Humans like to catch mackerel, too! You may be familiar with mackerel if you enjoy fishing as a hobby. Since they spend time in our coastal waters during the summer and early fall, they are a popular catch (and meal!) for recreational fishers from around Atlantic Canada. Unfortunately, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has classified mackerel in the critical zone, meaning that the stock has declined and needs rebuilding. However, we still don’t know a lot about the biology, ecology, and fishery operations for Atlantic mackerel. I think this seems like a great oppor-tuna-ty for fishers, scientists, and government officials to unite and work together to ensure that an abundance of these creatures can be found swimming our seas for years to come. If you’re interested in chatting all things mackerel, feel free to reach out at kayla.hamelin@dal.ca!

By Alex Tesar We here at the Back to the Sea Society hate to be accused of favouritism. When it comes to marine life, we love it all, from anemones to zooplankton. Jellyfish: yes. Whales—whale, of course. But there is one group of animals that may be entitled to bear the crown of nature’s most perfect creature. I speak, of course, of crabs. To understand why, we must first look at some things that aren’t crabs. Sorting the crabs from the crab-nots can be complicated. Consider, for example, the hermit crab: protruding eyes on stalks, a shell, and the trademark claws that suggest the quintessence of crabbiness. You would be forgiven for thinking that you were looking at a crab. However, despite their name, hermit crabs aren’t actually crabs. Though they resemble “true crabs,” hermit crabs are in fact a different kind of crustacean that happens to look very similar. And they are far from alone: among those living in disguise are the king crabs, which may have themselves evolved from hermit crabs (known, delightfully, as the “hermit-to-king” hypothesis), as well as hairy stone crabs and porcelain crabs. The king crab is not a crab, but it is a king. Photo credit: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017 The theory that crab-like crustaceans tend to evolve from non-crab ancestors is known as “carcinization.” The word literally means to become cancer-like, but think of the astrological sign, not the disease. The phenomenon was first described by a man named Lancelot Alexander Borradaile, who has perhaps one of the best names in the history of science. Borradaile coined the term while studying the evolution of the humble hermit crab, describing it as “one of the many attempts of Nature to evolve a crab.” Why does Nature want to evolve a crab so badly? Well, we know that evolution “selects” for traits that are particularly well-suited to a given environment, and there seems to be something about the crab-like shape that works very well when it comes to surviving and thriving in the water—so what works for “true crabs” might also evolve in other species that aren’t close genetic relatives. This is called parallel evolution. There are other examples of this in nature, too. In Australia, many marsupial species have evolved separately from mammals in the rest of the world but still look strangely familiar because they’ve faced similar evolutionary pressures—like the flying phalanger and the flying squirrel, which both glide from tree to tree. It appears that nature likes to get crabby. Of course, there’s no such thing as a perfect animal in evolution, only the creature that’s best adapted to its time and place. But when you come to the touch tank this summer, you can get hands-on and decide for yourself whether you are simply holding a hermit crab or touching a miracle. Via Twitter, @PattonPray

by Alisha Postma When you live and breath scuba diving, sooner or later you’re going to get the opportunity to dive into some pretty neat spots all over the world. Iceland, Greece, Egypt, Florida… My exotic scuba diving list is pretty extensive, but truth be told, as beautiful and picturesque as these dive destinations may be, as a Canadian diver, there is no place like home. For the past 6 years, I have lived in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Located on Canada’s east coast, Nova Scotia is the second smallest of ten provinces. It’s also a peninsula that is pretty much surrounded by Atlantic ocean. For cold water divers it’s paradise, and guess what? I’m proud to say it’s my paradise too! When you first look out into the North Atlantic it can be a bit unsettling. Cold, darkness, less than ideal visibility are a few things that immediately come to mind. But it only took me a few dives to figure out why when looking into our own backyards we can’t see the bottom - it’s because it’s so full of life. Ready to have your mind blown by the Canadian North Atlantic? It’s common to spot sculpin and sea ravens in the waters of Nova Scotia. This ruby red sea raven was photographed at the Paddy’s Head dive site, a favorite among the locals. With their dainty colors and itty-bitty bodies, nudibranchs are always a fun subject for macro shooters. While you can find nudi’s to shoot in Nova Scotia if you look really hard, they are much easier to find on Deer Island, New Brunswick. When photographing in Nova Scotia, I like to look for small critters like this funky little spiny lumpsucker. It gives the dive site some personality. Keep your eyes peeled because you never know what you will spy in the plant life. This rock crab decided to peek out for me on the green dead man’s fingers (scientifically known as Codium fragile). Striking red and pink colours are a sight for sore eyes in the cold productive waters of the Bay of Fundy. Here you will find brightly coloured anemones of all different shapes and sizes, with tentacles out trying to catch some food from the water column! Nothing spells Nova Scotia better than a close-up view of a lobster. You can find these arthropods all over the east coast scavenging the bottom on the hunt for their next meal. I love grabbing macro shots of these guys with a focal point on their beady little eyestalks. Plant, animal or lifeless rock? Chitons, also known as sea cradles, are a species of mollusk found exclusively in marine environments. On top of having the incredible power of surface adhesion, chitons have 8 separate shell plates that overlap and protect their otherwise soft body.

by Leah Robertson On both land, and in the ocean we are thankful for great dads! However, when we think of fish in the ocean, fish parental care may not immediately come to mind. But dads play a huge role in taking care of their offspring in the ocean! So in honour of father’s day, we have chosen two special fish-dads to highlight! Meet the rock gunnel: Photo: Leah Robertson This lil guy is often mistaken for an eel, but they are much smaller than that - only growing to 30cm! In this photo, father rock gunnel is guarding a cluster of eggs which are in the back of this very clever home - a bottle! Our second dad is the 3-spined stickleback, who will teach us all about the ways fish act as fathers. Photo: Leah Robertson This little fish can be found in our local fresh, coastal and brackish waters. They can be characterized by three tiny spikes on the top and the persistence of being a great father! The males of this fish work hard to build their nest to attract females, when their off springs are just a twinkle in their eye! They work to build these nests by digging a small pit, and then filling it with cozy ocean objects like algae to make it just right. After building their nest, they will do a zigzag dance to attract the female (seriously true!). If the fit is right, the soon to be momma will swim into the nest and lay her eggs. From there on out dad takes over in protecting the eggs, from fanning them often to creating little holes to ensure they are well ventilated soon to be tiny fish. Once the sticklebacks do hatch, dad will try to keep them around for a few days and if any try to wander away he will suck them up with his mouth and spit them back out near the nest. Talk about committed! We are whaley thankful for dads both on land and in the ocean! P.S. Special Father’s Day shout out to my own dad!

by Kaitlin Bureck It doesn’t happen regularly, but every once in a while, you will come across an animal that leaves you truly perplexed. There are animals that hold hands, throw punches, mimic leaves, change sexes, have two jaws, regenerate limbs, and have cube-shaped poop. If we were to rank* the perplexities that exist in the animal kingdom however, the top spot would belong to the cuTTlefish**. Not only do they have three hearts and can mimic the shape and texture of their surroundings, but they can also count better than human babies! For these reasons alone, cuTTlefish deserve to be a top contender for the prestigious Perplexity Prize but they have another surprising trick up their tentacle that really sets them apart. Photo by: Justin Gilligan Male cuTTlefish compete with one another to catch the attention of females in the hopes of mating with them. These competitions can be very aggressive and often involve barrel rolls, squirts of black ink, and an exchange of bites using hardened beaks. As is the case in many similar debacles, the larger male generally wins the fight. Ironically however, their efforts and injuries may not lead to a successful mating opportunity with observing females. This is because small male cuTTlefish are able to sneak past the fighting males by disguising as a female. The steps to doing so are pretty straightforward, (1) mimic muted female colours, (2) tuck in their tentacles to appear as if they are carrying eggs, and (3) rely on their smaller size. Once they get past the larger competitive males, the smaller males will reveal themselves to the females by turning on a colourful display and, well, you know what happens next. So, there you have it, an animal whose perplex, peculiar, and puzzling abilities are worthy or recognition and celebration. I challenge you to embody the cuTTlefish – the ultimate trickster – on this special day. I myself, am looking forward to challenging babies to counting contests. * Every animal is beautiful and unique in its own way ** Although I cannot comment about whether these animals like cuddling, I can confirm that these animals are not referred to as cuddlefish Kaitlin is a member of our Communications Committee. See her last blog post "It's Raining Adaptations, Hallelujah!" here. by Kaitlin Burek When it is raining, I take out my boots and jacket. When it is snowing, I add a scarf and some mittens. When it is windy, I increase my layers and quicken my steps. It is safe to say, that since I moved to the Maritimes, I have adapted to the changing – often unexpected – weather conditions. My usual response to downpours, blizzards, and wind storms is to stay inside with a bag of storm chips and peak out the window to see how nature is fairing. My view consists of trees, buildings, and the unfortunate person that didn’t reach shelter in time. What I can’t see from my window during these weather events is the ocean, but I can envision the swell and the crashing waves. What is harder to imagine is how our beloved ocean organisms survive – animals and algae alike! Winter storms in Eastern Passage. The intertidal zone in Nova Scotia is characterized by things like crabs, snails, mussels, barnacles, and rockweed. These animals are not often described as being hardy, but they should be, as their adaptations allow them to survive in a very volatile environment. The environment is difficult because not only do these animals have to deal with stressors that originate in the ocean, but they also must worry about what comes from the land and atmosphere – eek! Some animals, like crabs, find protection by hiding in cracks or under boulders while others, like snails, carry protection on their back. Snails heading for the cracks! Photo by Kaitlin. Nonmobile animals also have found creative ways to adapt to stormy weather; mussels are streamlined, hold onto stable rocks using fine threads, and huddle together; barnacles close their calcareous bodies; and rockweed holds on tight to rock with fancy-dancy* discoid anchoring structures. Whether it is a behavioural or a physical adaptation, the intertidal ocean organisms are designed to survive and thrive! * Although I wish I could tell you differently, this is not a scientific term. Use with caution. Mussels clumping. Photo by Kaitlin. If we were to move deeper into the subtidal, not only would the organisms change, but so would the impact of weather events. If the seabed is further from the ocean surface, it is less impacted by the weather – think of the depth as a kind of buffer zone. Since the organisms are less impacted, they do not dedicate as much energy into weather-protective adaptations. You still see adaptations however; sea stars don suction cup-like tube feet and other benthic invertebrates remain streamlined. The organism’s primary concern in the subtidal, unlike the intertidal, is not to adapt to weather but instead put energy into fleeing predators and finding food – how cool! If we were to go deeper in the ocean you may notice some differences that exist between that ecosystem and the one that exists in the intertidal and the subtidal. First off, it is dark, I mean no-sun-is-penetrating dark, and it is cold. What you will not notice however, is sloshing water caused from overhead weather events. Other than debris falling from surface waters, there would be no evidence of a weather event because wave energy does not attenuate deep enough to impact the organisms that live there. So, my advice to you is if you really want to escape Maritime weather events you should hop, skip, and jump to the bottom of the ocean. Happy splashing!

This Valentine's Day, our Communications Committee members came together to let their favourite ocean animals know just how much they care for them. Read on for some pun-filled entertainment and fun facts! I'm Not Squiddin' You Valentine!Before my time at Back to the Sea I worked for the Petty Harbour Mini Aquarium. For my first interview there, I was told to bring a prop and talk about an ocean animal. I knew I couldn’t bring a live octopus, so I settled for its North Atlantic cousin - the squid! From that moment forward, it was an inky love affair. As highly intelligent creatures, cephalopods continually amaze scientists with their ability to understand, learn and even go so far as to escape their tanks! We love to do squid dissections to not only feed our animals, but also to teach our visitors all about these slimy (and at times smelly) creatures. I have been known to write squid ink letters, and maybe if you are so lucky at the Touch Tank Hut you can have one too! - Leah A squid dissection demo by Leah for kids at the Touch Tank Hut!

|

Categories

All

We send blog recaps with in all our quarterly newsletters!

|