|

Imagine a motorcycle revving through your house while you get ready for school, make a meal, or talk to your family. That motorcycle would be loud, kick up dirt everywhere, and make it difficult to do the things you normally do. No one signs up for that! That is a taste of what marine creatures in the Halifax Harbour have been experiencing for decades. Big container ships, recreational boats, and ferries drive through their living rooms, making lots of noise and polluting their space. Fortunately, the Halifax Harbour will be changing soon! However, before we talk about the good things coming our way, we need to talk about why things need to change – we need to talk about how animals in the Halifax Harbour are affected by noise pollution. Halifax Harbour on a still morning (image credit: Charlotte Craig) Whales are heavily impacted by boat noise, because they use echolocation to find their food and move around the ocean. Echolocation is when animals like whales and dolphins send out sounds in the water, and listen for those sounds to echo back to them, helping them figure out what is around them. While whales are rare visitors to the Harbour, some more common creatures are affected by noise, too. Animals that you see in the Touch Tank Hut like crabs and urchins can also be affected by noise. Noise pollution can reduce all marine creature’s ability to communicate, navigate, locate prey, avoid predators, and find mates. Ecological acts that are key to ocean health that are performed by invertebrates, such as water filtration and mixing sediment layers, are also negatively affected by noise. Overall, noise stresses animals out and it stops them from doing all the things that they normally would. Boats can also cause silt (ocean floor dirt) to be turned up which can make moving around very tricky. Boats can also leave behind unwanted fuel and other pollutants while they move through the water. Thankfully, our sea friends will soon be catching a small break. Electric ferries are coming to the Halifax Harbour starting in 2022. Electric ferries are quieter and don’t use gas. Hooray! A Halifax Harbour ferry (image credit: Discover Halifax) The new ferries will run on a new route from the Halifax terminal to a new terminal in Mill Cove. While it is only a small step in the right direction, hopefully it will lead to the province adopting more electric ferries and other transportation. Maybe one day, the Halifax-Alderney route will be electric, and the Touch Tank Hut residents will be spared the noise. Just as we must wash our hands and keep our voice down in the Touch Tank Hut, it’s about time we start keeping the water clean and quiet for out ocean buddies in the Harbour!

0 Comments

by Kayla Hamelin When you live in Nova Scotia, it is obvious that fishing is an important part of the culture and economy of Atlantic Canada. Fishing vessels fill our harbours. Folks head down to their local pier – rod in hand - to cast a line and see what bites. Seafood restaurants and markets abound. People fish for fun, for food, and for work. As I begin my PhD research in fisheries science, I am gaining a greater appreciation for the wide range of species harvested off our shores. Out there under the “big blue blanket” are incredible invertebrates like the gangling snow crab, and formidable flatfish like the massive Atlantic halibut. However, there is one species that has really charmed me – the Atlantic mackerel, also known as Scomber scombrus. The more I learn about these fin-tastic friends, the more I am hooked! Mackerel are a marine, pelagic fish, which means that they live in the open water column of the ocean, rather than on the bottom or at the shore. They have beautiful bodies well-adapted for camouflage in the ocean, with shimmery blue on their backs, silvery undersides, and squiggly stripes down their backs and flanks. You may notice the tiny finlets (mini, nonretractable fins) on their caudal peduncle (a funky name for the area where the body meets the tail fin). These finlets help with their high-performance swimming and are a feature shared with some of the larger members of their Scombridae family, including the mighty tunas and bonitos. Mackerel are relatively small, measuring up to about 40 cm (a bit more than a foot) in length and about 1 kg in mass. However, there is strength in numbers, and these schooling fish like to swim together in large groups to stay safe from predators. Fun fact: unlike many of their relatives, mackerel do not have a swim bladder, the gas-filled organ that helps many fish to control their buoyancy. Without a swim bladder, mackerel must follow Dory’s advice and just keep swimming! Atlantic mackerel can be found on both sides of the Atlantic, so we share this special species with our friends in Europe. Here in North America, they range from the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador in the north all the way down to North Carolina in the south. Mackerel always play an important role in the marine ecosystem. They are known as “forage fish” because they act as an important food source for larger animals such as marine mammals, sharks, and other larger fish. Mackerel themselves prefer to eat small invertebrates such as zooplankton. As a result, they act as an important link in the ecosystem, passing food energy up through the food web to the top marine predators. Humans like to catch mackerel, too! You may be familiar with mackerel if you enjoy fishing as a hobby. Since they spend time in our coastal waters during the summer and early fall, they are a popular catch (and meal!) for recreational fishers from around Atlantic Canada. Unfortunately, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has classified mackerel in the critical zone, meaning that the stock has declined and needs rebuilding. However, we still don’t know a lot about the biology, ecology, and fishery operations for Atlantic mackerel. I think this seems like a great oppor-tuna-ty for fishers, scientists, and government officials to unite and work together to ensure that an abundance of these creatures can be found swimming our seas for years to come. If you’re interested in chatting all things mackerel, feel free to reach out at kayla.hamelin@dal.ca!

by Alisha Postma When you live and breath scuba diving, sooner or later you’re going to get the opportunity to dive into some pretty neat spots all over the world. Iceland, Greece, Egypt, Florida… My exotic scuba diving list is pretty extensive, but truth be told, as beautiful and picturesque as these dive destinations may be, as a Canadian diver, there is no place like home. For the past 6 years, I have lived in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Located on Canada’s east coast, Nova Scotia is the second smallest of ten provinces. It’s also a peninsula that is pretty much surrounded by Atlantic ocean. For cold water divers it’s paradise, and guess what? I’m proud to say it’s my paradise too! When you first look out into the North Atlantic it can be a bit unsettling. Cold, darkness, less than ideal visibility are a few things that immediately come to mind. But it only took me a few dives to figure out why when looking into our own backyards we can’t see the bottom - it’s because it’s so full of life. Ready to have your mind blown by the Canadian North Atlantic? It’s common to spot sculpin and sea ravens in the waters of Nova Scotia. This ruby red sea raven was photographed at the Paddy’s Head dive site, a favorite among the locals. With their dainty colors and itty-bitty bodies, nudibranchs are always a fun subject for macro shooters. While you can find nudi’s to shoot in Nova Scotia if you look really hard, they are much easier to find on Deer Island, New Brunswick. When photographing in Nova Scotia, I like to look for small critters like this funky little spiny lumpsucker. It gives the dive site some personality. Keep your eyes peeled because you never know what you will spy in the plant life. This rock crab decided to peek out for me on the green dead man’s fingers (scientifically known as Codium fragile). Striking red and pink colours are a sight for sore eyes in the cold productive waters of the Bay of Fundy. Here you will find brightly coloured anemones of all different shapes and sizes, with tentacles out trying to catch some food from the water column! Nothing spells Nova Scotia better than a close-up view of a lobster. You can find these arthropods all over the east coast scavenging the bottom on the hunt for their next meal. I love grabbing macro shots of these guys with a focal point on their beady little eyestalks. Plant, animal or lifeless rock? Chitons, also known as sea cradles, are a species of mollusk found exclusively in marine environments. On top of having the incredible power of surface adhesion, chitons have 8 separate shell plates that overlap and protect their otherwise soft body.

by Leah Robertson On both land, and in the ocean we are thankful for great dads! However, when we think of fish in the ocean, fish parental care may not immediately come to mind. But dads play a huge role in taking care of their offspring in the ocean! So in honour of father’s day, we have chosen two special fish-dads to highlight! Meet the rock gunnel: Photo: Leah Robertson This lil guy is often mistaken for an eel, but they are much smaller than that - only growing to 30cm! In this photo, father rock gunnel is guarding a cluster of eggs which are in the back of this very clever home - a bottle! Our second dad is the 3-spined stickleback, who will teach us all about the ways fish act as fathers. Photo: Leah Robertson This little fish can be found in our local fresh, coastal and brackish waters. They can be characterized by three tiny spikes on the top and the persistence of being a great father! The males of this fish work hard to build their nest to attract females, when their off springs are just a twinkle in their eye! They work to build these nests by digging a small pit, and then filling it with cozy ocean objects like algae to make it just right. After building their nest, they will do a zigzag dance to attract the female (seriously true!). If the fit is right, the soon to be momma will swim into the nest and lay her eggs. From there on out dad takes over in protecting the eggs, from fanning them often to creating little holes to ensure they are well ventilated soon to be tiny fish. Once the sticklebacks do hatch, dad will try to keep them around for a few days and if any try to wander away he will suck them up with his mouth and spit them back out near the nest. Talk about committed! We are whaley thankful for dads both on land and in the ocean! P.S. Special Father’s Day shout out to my own dad!

This Valentine's Day, our Communications Committee members came together to let their favourite ocean animals know just how much they care for them. Read on for some pun-filled entertainment and fun facts! I'm Not Squiddin' You Valentine!Before my time at Back to the Sea I worked for the Petty Harbour Mini Aquarium. For my first interview there, I was told to bring a prop and talk about an ocean animal. I knew I couldn’t bring a live octopus, so I settled for its North Atlantic cousin - the squid! From that moment forward, it was an inky love affair. As highly intelligent creatures, cephalopods continually amaze scientists with their ability to understand, learn and even go so far as to escape their tanks! We love to do squid dissections to not only feed our animals, but also to teach our visitors all about these slimy (and at times smelly) creatures. I have been known to write squid ink letters, and maybe if you are so lucky at the Touch Tank Hut you can have one too! - Leah A squid dissection demo by Leah for kids at the Touch Tank Hut!

|

| Meghan serves on Back to the Sea's Communications Committee and volunteers her time with our organization in many other ways. She is a graduate of the Master of Marine Management program and works as a Conservation Assistant at the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society- Nova Scotia chapter. You can read Meghan's blog “Lautanas” here. |

Text and Photos by Emilie Novaczek

Spoon Cove, Newfoundland

There’s lots to see while SCUBA diving the North Atlantic coast; long-toothed wolffish, scowling eelpouts, graceful winter skates, fields of magenta coralline algae, and if you’re lucky, a glimpse of a humpback whale in the distance. In all that diversity, the sea urchins are some of my favourites – and it’s all about the hats.

The most common urchin in Newfoundland, and throughout the Maritimes, is Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis, a bit of a mouthful for the unassuming green urchin. We see hundreds of green urchins on every dive, and in the shallows, we find them covered with anything they can get their tube feet on: rocks, shells, even the odd golf ball.

The most common urchin in Newfoundland, and throughout the Maritimes, is Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis, a bit of a mouthful for the unassuming green urchin. We see hundreds of green urchins on every dive, and in the shallows, we find them covered with anything they can get their tube feet on: rocks, shells, even the odd golf ball.

St. Thomas Cove, Newfoundland. Photo by Christopher Power

Echinodermata refers to the phylum of animals that includes seastars, sea cucumbers, sand dollars, crinoids, and our hat-wearing urchins. Echinoderms share a few key features, including a couple that sound like superheroes: Wolverine’s regeneration and Spiderman’s ability to scale smooth surfaces at any angle. We’ll get back to regeneration later on.

Echinoderms move around the seafloor (or simply move food to their mouth) using hundreds of sticky tube feet. These feet are part of the water-vascular system, a network of seawater-filled tubes. Urchins move using the tube feet on their ventral side by contracting small muscles that force water into the tubefoot to take each step. The end of each tube foot is very, very sticky. They are often described as suction cups, however recent research[1] indicates that echinoderms likely use a bio-adhesive, rather than suction, to achieve their Spiderman-like climbs.

Urchins also use these sticky tube feet to pick up and hold onto rock, shells, golf balls, and other treasures.

But why?

Spoon Cove, Newfoundland

Behavioural ecologists call urchin hats “covering behaviour”. That name is related to the first and most prevalent hypotheses about the phenomena: the urchins are covering themselves to provide shelter from sunlight, predators, or both.

Experiments conducted on Paracentrotus lividus, the purple sea urchin common to the Eastern Atlantic Ocean, confirmed the light hypothesis. Researchers in Ireland found that when the urchins were exposed to full spectrum UV light, more individuals would pick up their hats and/or move to the shady corners of their tanks to avoid harmful UV radiation[2].

Around the same time, another scientist in California was studying covering behaviour of Pacific rose flower urchins, Toxopneustes roseus[3]. The rose urchin study wasn’t conducted in a lab; instead urchin behaviour was observed in their natural habitats. What they found was that at the sample site with the greatest wave energy, there was also the most covering behaviour among the urchins.

Experiments conducted on Paracentrotus lividus, the purple sea urchin common to the Eastern Atlantic Ocean, confirmed the light hypothesis. Researchers in Ireland found that when the urchins were exposed to full spectrum UV light, more individuals would pick up their hats and/or move to the shady corners of their tanks to avoid harmful UV radiation[2].

Around the same time, another scientist in California was studying covering behaviour of Pacific rose flower urchins, Toxopneustes roseus[3]. The rose urchin study wasn’t conducted in a lab; instead urchin behaviour was observed in their natural habitats. What they found was that at the sample site with the greatest wave energy, there was also the most covering behaviour among the urchins.

Harbour Grace, Newfoundland

So which is it? Sun safety? Or are these hats more like seat belts and kneepads, weighing urchins down and protecting them from wave damage?

On this side of the Atlantic, researchers tested several factors simultaneously to trace the covering behaviour to it’s source. In a laboratory, green urchins were exposed to common predators, wave surge, waving algae blades, and sunlight[4]. As it turns out, the predators were a bust: their presence had no significant impact on the rate of covering behaviour.

The hats are not camouflage.

On this side of the Atlantic, researchers tested several factors simultaneously to trace the covering behaviour to it’s source. In a laboratory, green urchins were exposed to common predators, wave surge, waving algae blades, and sunlight[4]. As it turns out, the predators were a bust: their presence had no significant impact on the rate of covering behaviour.

The hats are not camouflage.

Urchins may have some scary looking spines, but they still have predators!

Like the Irish purple urchins, green urchins exposed to UV light were found to cover up more. However, UV exposure wasn’t the most important factor. This study found that green urchins on the east coast of Canada, like rose urchins in California, wore more hats when they were exposed to wave surge, and/or in contact with moving algae blades.

Not all urchins wear hats though; the Canadian study found that smaller urchins were more like to cover up.

Seastars can regenerate lost arms, sometime many at a time (see? I told you we’d get back to this). Though it’s less dramatic, urchins are constantly regenerating lost and broken spines. But regeneration takes energy. It may be a safer bet, particularly for a small urchin who is vulnerable to dislodgement and damage, to pick up some extra weight and a little sun protection at the same time.

Not all urchins wear hats though; the Canadian study found that smaller urchins were more like to cover up.

Seastars can regenerate lost arms, sometime many at a time (see? I told you we’d get back to this). Though it’s less dramatic, urchins are constantly regenerating lost and broken spines. But regeneration takes energy. It may be a safer bet, particularly for a small urchin who is vulnerable to dislodgement and damage, to pick up some extra weight and a little sun protection at the same time.

Bacon Cove, Newfoundland

[1] More information on tube feet: http://echinoblog.blogspot.ca/2013/01/echinoderms-dont-suck-they-stick.html

[2] Verling et al. 2002: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs002270100689?LI=true

[3] James 2000: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs002270000423?LI=true

[4] Dumont et al. 2007: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347207000796

[2] Verling et al. 2002: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs002270100689?LI=true

[3] James 2000: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs002270000423?LI=true

[4] Dumont et al. 2007: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347207000796

Emilie is a marine conservation biologist and PhD candidate at the Memorial University of Newfoundland. She is also the Chair of the Biology Graduate Student Association at Memorial. Emilie knows all about catch-and-release aquariums as she has been a volunteer scientific diver for the Petty Harbour Mini Aquarium for the past four years. t: @maptheblue

Thanks so much for writing this post Emilie. We can only hope you'll be able to join us on a Back to the Sea dive one day!

P.S. Another thing we love about Emilie are her awesome pictures, like this one of an urchin's mouth, known as Aristotle's Lantern.

Thanks so much for writing this post Emilie. We can only hope you'll be able to join us on a Back to the Sea dive one day!

P.S. Another thing we love about Emilie are her awesome pictures, like this one of an urchin's mouth, known as Aristotle's Lantern.

This month we wrote a blog post for the Canadian Network for Ocean Education. Click below to read it!

Interpreting at the Petty Harbour Mini Aquarium in Newfoundland.

By Dr. Chris Harvey-Clark

This guest post is brought to you by Dr. Chris Harvey-Clark who is the University Veterinarian as well as the Director of Animal Care in the Department of Psychology at Dalhousie University. In an interview on CBC's Mainstreet program, Dr. Harvey-Clark spoke to the success of small-scale aquarium such as the ones found in St. Andrew's, New Brunswick and Petty Harbour, Newfoundland. We reached out to him following this interview at which point Dr. Harvey-Clark agreed to serve as one of our valuable advisors. He has taken the time to tell us more about one of his areas of interest in the post below.

People might be surprised to know that a big marine predator that kills fish using electrical shock is coming in increasing numbers to shallow waters around Nova Scotia!

This late summer visitor is the Atlantic torpedo ray, Tetronarce (formerly Torpedo) nobiliana, a large, enigmatic member of the skate and ray family (the Batoids) found from tropical to temperate waters on both sides of the North Atlantic inshore and in deep waters. By far the largest of 17 species of electric rays worldwide, the torpedo ray can weigh 90kg and have a body disc diameter approaching 2m in mature females.

This species uses electrogenic organs comprised of modified muscle cells in the lateral margins of the body disc to generate controlled DC current bursts in excess of 200 volts. This shocking power can snap the back of a mackerel in tetanic convulsions and is also used for discouraging predators. A friend of mine who was shocked by this species while diving lived to tell the tale and likened the sensation to putting your finger into a dryer socket.

This late summer visitor is the Atlantic torpedo ray, Tetronarce (formerly Torpedo) nobiliana, a large, enigmatic member of the skate and ray family (the Batoids) found from tropical to temperate waters on both sides of the North Atlantic inshore and in deep waters. By far the largest of 17 species of electric rays worldwide, the torpedo ray can weigh 90kg and have a body disc diameter approaching 2m in mature females.

This species uses electrogenic organs comprised of modified muscle cells in the lateral margins of the body disc to generate controlled DC current bursts in excess of 200 volts. This shocking power can snap the back of a mackerel in tetanic convulsions and is also used for discouraging predators. A friend of mine who was shocked by this species while diving lived to tell the tale and likened the sensation to putting your finger into a dryer socket.

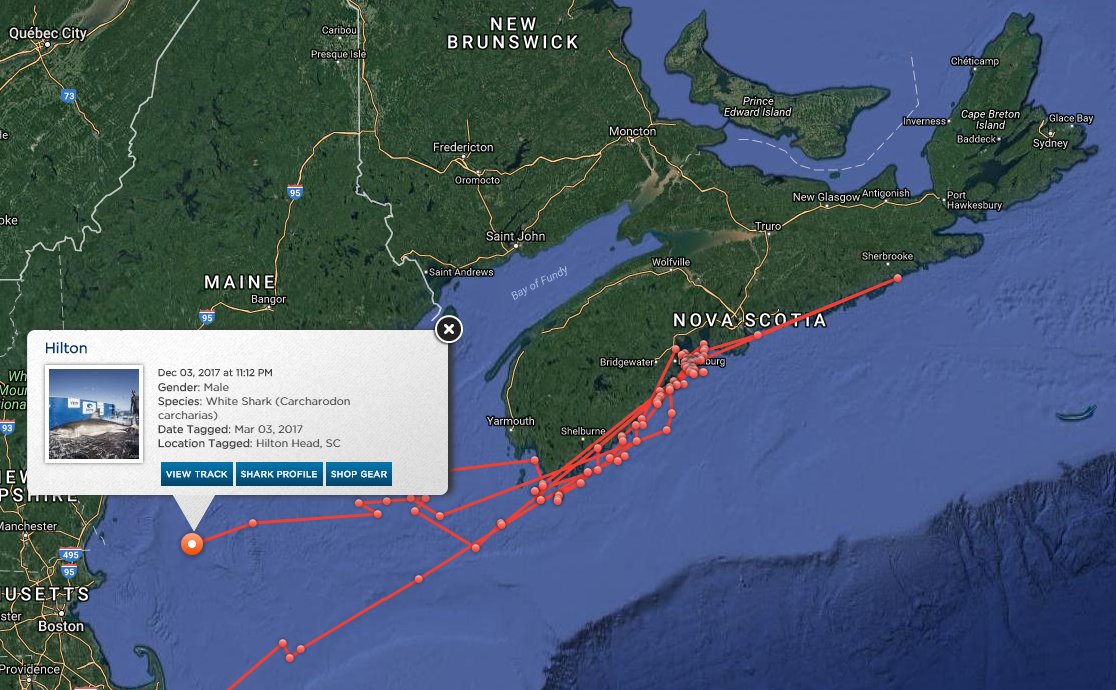

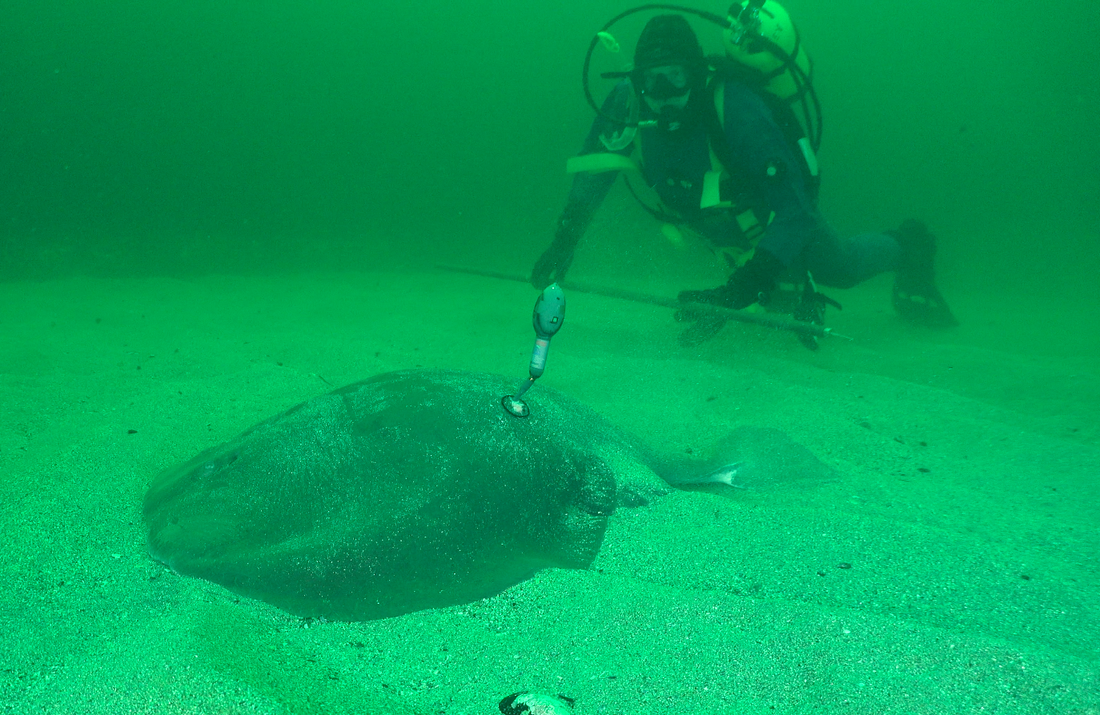

Dr. Fred Whoriskey views the first ever satellite tagged Atlantic torpedo ray

Photo credit: Dr. Chris Harvey-Clark

Photo credit: Dr. Chris Harvey-Clark

The electrogenic tissues of torpedo rays have been extensively studied at the cellular and molecular level, with thousands of citations in the scientific literature. Some of the earliest work on the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and its effects on muscle tissue were first characterized in torpedo ray tissues. It is a paradox that despite extensive study at the cellular level, little is known of the ecology, movement and behaviour of T. nobiliana. In fact, decades of fishing for use in neuroscience research depleted local populations of this species in the vicinity of the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole Mass.

The fact remains that virtually nothing is known about the basic biology of T. nobiliana. The size and age structure of the Atlantic population, depth, substrate and temperature preferences, onshore/offshore movements of this species, prey preferences, longevity, reproductive parameters and life cycle are all poorly known.

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List indicates the species is data deficient, in common with the majority of sharks, skates and rays. In this respect, our knowledge of T. nobilana resembles the former state of knowledge of many large charismatic species such as sharks, tunas, sea turtles and many marine mammal species prior to the development of modern electronic tracking technology beginning two decades ago.

Like the curious case of the dog that failed to bark in the night, the fact that this species is rarely reported as bycatch despite intense commercial fishing within its known range begs the question: where do these animals go? What is their role in the seasonal summer assemblage of large pelagic and forage fish species that occurs in boreal seas around Europe and North America annually?

The fact remains that virtually nothing is known about the basic biology of T. nobiliana. The size and age structure of the Atlantic population, depth, substrate and temperature preferences, onshore/offshore movements of this species, prey preferences, longevity, reproductive parameters and life cycle are all poorly known.

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List indicates the species is data deficient, in common with the majority of sharks, skates and rays. In this respect, our knowledge of T. nobilana resembles the former state of knowledge of many large charismatic species such as sharks, tunas, sea turtles and many marine mammal species prior to the development of modern electronic tracking technology beginning two decades ago.

Like the curious case of the dog that failed to bark in the night, the fact that this species is rarely reported as bycatch despite intense commercial fishing within its known range begs the question: where do these animals go? What is their role in the seasonal summer assemblage of large pelagic and forage fish species that occurs in boreal seas around Europe and North America annually?

The habit and habitat of this species remains a mystery. Observations exist of occasional individuals in shallow water sand and mud bottom habitats from Nova Scotia to the Florida keys and from northern Scotland to West Africa, into the Mediterranean, usually from fisheries bycatch inside continental shelf depths. Fishbase and similar database sources cite depth data for this species from shallow water to 800 meters and report their presence as rare fisheries bycatch in the Mediterranean. Several references claim the rays are benthic bottom dwellers when younger and become more pelagic dwellers as they get older, but there is little evidence in the primary scientific literature to support this claim.

In the fall of 2015, Dr. Fred Whoriskey and myself tagged a female Atlantic torpedo ray with a satellite tag near Halifax, NS. The tag was programmed to pop up to the surface 95 days later, and report its position and other data to a geosynchronised satellite. I had theorized that the rays were following the shallow continental shelf migrations of forage fish like herring and mackerel - north in the summer and south in the winter. Imagine my surprise when the tag reported 95 days later from an offshore location over 900 km out in the North Atlantic, from an area where the bottom is in excess of 4000 m. This single record indicated that in at least one case, this species does in fact act as a pelagic animal, quite amazing for a ray we had found dug in to the bottom while scuba diving in 20 m of water.

This discovery has led to plans for a more extensive study of the movement and behaviour of this species. Volunteers interested in helping the torpedo ray tagging team can contact me at Dalhousie University: chclark@dal.ca.

In the fall of 2015, Dr. Fred Whoriskey and myself tagged a female Atlantic torpedo ray with a satellite tag near Halifax, NS. The tag was programmed to pop up to the surface 95 days later, and report its position and other data to a geosynchronised satellite. I had theorized that the rays were following the shallow continental shelf migrations of forage fish like herring and mackerel - north in the summer and south in the winter. Imagine my surprise when the tag reported 95 days later from an offshore location over 900 km out in the North Atlantic, from an area where the bottom is in excess of 4000 m. This single record indicated that in at least one case, this species does in fact act as a pelagic animal, quite amazing for a ray we had found dug in to the bottom while scuba diving in 20 m of water.

This discovery has led to plans for a more extensive study of the movement and behaviour of this species. Volunteers interested in helping the torpedo ray tagging team can contact me at Dalhousie University: chclark@dal.ca.

By Ruby Banwait

I’m a west coast girl to my core. I grew up in what was at the time, a small fishing and farming community in the mouth of the mighty Fraser River. I spent countless hours playing in tide pools and splashing around the emerald sea. Few things give me greater joy. However, in 2012 when I traveled across the country to discover the deep blue of the Atlantic Ocean around St. John’s, Newfoundland, I realized just how easy it is to fall in love with any Canadian coastline. So when I had the opportunity to travel to the Maritimes in June of this year, I simply couldn’t pass it up!

I’m a west coast girl to my core. I grew up in what was at the time, a small fishing and farming community in the mouth of the mighty Fraser River. I spent countless hours playing in tide pools and splashing around the emerald sea. Few things give me greater joy. However, in 2012 when I traveled across the country to discover the deep blue of the Atlantic Ocean around St. John’s, Newfoundland, I realized just how easy it is to fall in love with any Canadian coastline. So when I had the opportunity to travel to the Maritimes in June of this year, I simply couldn’t pass it up!

Ruby spotting her first iceberg in St. John's, Newfoundland

Halifax is a fun place boasting more pubs per capita than any other city in Canada. Visiting from Vancouver, which caters to foodies and desperately tries to be the country’s “greenest” city, I was elated to find organics receptacles beside every garbage and recycling bin as well as some great vegetarian restaurants. My only regret is not dining in Nova Scotia before becoming a vegetarian. I’m sure I missed out on some of the best lobster dishes around!

The invitation to visit Halifax and stay with good friends in their seaside home combined with scouting out locations for a new mini aquarium while adventuring around the beautiful province couldn’t have been a sweeter combination for this fish geek.

Nova Scotia is rich in maritime history yet there are few places where you can meet live marine animals that call this part of the world home. What better location for the Back to the Sea Society to build a mini aquarium than within the greater Halifax area? As the founding curator and general manager of the Petty Harbour Mini Aquarium in Newfoundland, I felt honoured to be included in the search for potential homes of the Back to the Sea Mini Aquarium! I couldn’t be more excited to see the perfect location that Magali has found for her seasonal, hands-on, conservation and education based facility. Stay tuned!

The invitation to visit Halifax and stay with good friends in their seaside home combined with scouting out locations for a new mini aquarium while adventuring around the beautiful province couldn’t have been a sweeter combination for this fish geek.

Nova Scotia is rich in maritime history yet there are few places where you can meet live marine animals that call this part of the world home. What better location for the Back to the Sea Society to build a mini aquarium than within the greater Halifax area? As the founding curator and general manager of the Petty Harbour Mini Aquarium in Newfoundland, I felt honoured to be included in the search for potential homes of the Back to the Sea Mini Aquarium! I couldn’t be more excited to see the perfect location that Magali has found for her seasonal, hands-on, conservation and education based facility. Stay tuned!

Interpreting a tank at the Petty Harbour Mini Aquarium

One of the highlights of our trip was an extensive private tour of Hope for Wildlife, an animal rescue and rehab center located in Seaforth, Nova Scotia. I watch the show on the Knowledge Network and even PVR it so I don’t miss any episodes. Yes, it’s true. This fish geek is just a lover of all animals. Thanks to Alison Dube for an absolutely wonderful tour. I got to cuddle a three legged skunk named Maxwell and discovered I have a great love for porcupines. Special thanks to all the staff and volunteers at Hope for Wildlife for your dedication to animals and passion for better wildlife education!

Look out for the Back to the Sea Society’s marine animal touch tanks at the Hope for Wildlife Open House on August 28th.

Look out for the Back to the Sea Society’s marine animal touch tanks at the Hope for Wildlife Open House on August 28th.

Hope, Ruby and Maxwell the three-legged skunk

My time in Nova Scotia was entirely too short and I was already looking forward to a return visit before I even left. This is a province not to be missed!

Ruby Banwait is an Aquarium Biologist at the Vancouver Aquarium and was the founding Curator and General Manager at the Petty Harbour Mini Aquarium. She is one of Back to the Sea's valuable advisors. We are so thankful to her for taking time during her vacation to scout locations for the future Back to the Sea Aquarium and for contributing to the blog.

Categories

All

Collect Hold And Release

Cool Species!

Cool Species Algae!

Cool Species - Algae!

Events

Field Work

Guest Post

In The News

Plogging

Touch Tank Hut

We send blog recaps with in all our quarterly newsletters!